2016-17 Alligator Juniper Contest!

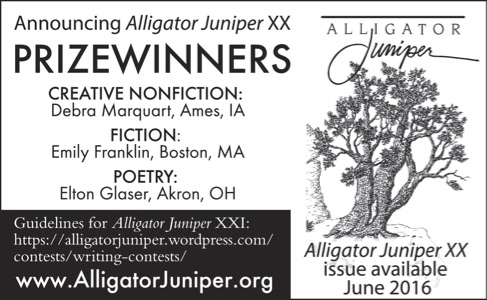

Posted: September 12, 2016 Filed under: Alligator Juniper, Uncategorized Leave a commentRead an Excerpt from Emily Franklin’s Prizewinning Story, “Qualities of the Modern Farmer”

Posted: April 20, 2016 Filed under: Alligator Juniper Leave a commentForthcoming in AJ XX

The field at night smelled partly like pie baking in the end of summer, scent elbowing its way through the grass alleys, and partly like something dying. The last thing Miller made before testing endless pecan recipes was a dessert: baked damson plums, brown sugar scorched on top, with a heavy slop of cream. He’d scooped the wilted fruit into a chipped mug for his father and brought it upstairs to the side bedroom and stood there bedside with his knuckles burning as they pressed into the mug’s too-small handle.

There was his father, sheets shitty and damp, food in his beard though he hadn’t eaten in days. At the end, Miller had frozen chicken stock in an ice tray and held a cube in his fingertips as his father tried to suckle it. The season was just starting then. Out the window Miller had watched the green nudging him, the nuts whispering to him that this was now his, every last bud on all twenty-nine hundred trees, the largest farm in Walbarger County, everything needing his supervision.

“Who’s there?” Miller asked, getting up from his folding chair. He knew it could be someone or nothing. Around harvest, the pecans seemed their own society, able to communicate with odd twisting sounds, the lazy breeze loping between them, creating conversation that Miller struggled to understand.

No answer. Miller swallowed more Nubit, toyed with the idea of bottling it for retail, creating small armies of snack mixes, liquors, and oils. Hadn’t he dreamed of working a cash register as a kid? He could set up a shop in one of the outbuildings, do it up with curtains and a sign out front, take the farm to the next level with tours and products for shipping. Just as fast as he’d designed the store in his mind and typeset a brochure, he imagined standing up, setting everything down—gun, Nubit, even his coat—and walking away from the place for good, away from the life he’d inherited under duress.

Read an Excerpt from Debra Marquart’s Prizewinning Essay, “When the Band Broke Up”

Posted: April 6, 2016 Filed under: Alligator Juniper Leave a commentForthcoming in AJ XX

When the band broke up, I turned worn circles in the shag carpet of my basement efficiency apartment on Fargo’s north side until the electricity went out, then I bought a newspaper and circled job ads that matched my marketable skills.

When the band broke up, I turned worn circles in the shag carpet of my basement efficiency apartment on Fargo’s north side until the electricity went out, then I bought a newspaper and circled job ads that matched my marketable skills.

“Receptionist,” I circled. Quick learner. Can answer phones; fast and accurate typist. What else could I put on the application? Sleeps well in moving vehicles; looks good in spandex and leather.

And to think that in high school, I was voted “Most Talented” and “Most Likely to Succeed.” When our choir director, Mr. Mosbrucker, discovered I could sing notes above C6, he gave me the coloratura soprano solos and sent me off to state competitions.

No one other than Mr. Mosbrucker and the judges at state seemed impressed by the clarity of my whistle register or my three and a half octaves. I still had to do the dishes. I still cheered my voice to hoarseness at basketball games and got colds without worry and yelled for the cows to come home from the pasture.

Those rare notes rode around inside my body like cloistered jewels. Some people can make their eyes move independently of one another, some people can bend their thumbs all the way back to their forearms. I can sing fast arpeggios in the highest tessitura of pitches written for the human voice.

No one ever said, “Be careful, dear, you must guard your vocal cords.”

Read an Excerpt from Elton Glaser’s Prizewinning Poem, “Morning with Injured Air”

Posted: April 5, 2016 Filed under: Alligator Juniper Leave a commentForthcoming in AJ XX

What kind of dreams seep up from downy pillows?

Women in all their flesh and finery,

Swivel of bellies, long legs whistling with silk.

Thank God, it’s too soon

For the bronze appeal of church bells.

Isn’t silence sweeter to heaven than those brute tongues?

Hair at odds with itself, I wrangle a Lucky

From the wrecked pack, and pour into my mug

Black acid from the day before.

I wish this milk came from cows

With the map of Europe on their bony rumps,

And these eggs from peahens in a pear tree.

I want a morning strange as gypsy earrings

On a nun, anything to make my heart

Backfire and grind into second gear.

Read an Excerpt from K.L. Cook’s Essay “Las Vegas Transcendentalists” in AJ’s Gallery 2015 ON SALE NOW

Posted: June 24, 2015 Filed under: Alligator Juniper Leave a commentFrom K.L. Cook’s Essay “Las Vegas Transcendentalists”

There are times in our lives when we are ripe for transformation.

The job looked simple enough. The “boys” brought towels to the guests, took their drink or snack orders, rubbed suntan lotion on their backs. Most of the sunbathers were older women, wearing one-piecers and straw hats and big sunglasses, fruity umbrella drinks in hand. A few bikinied women flipped themselves regularly like hamburgers on a grill. The cash, sometimes fives and tens, changed hands, the “boys” palming the cash easily, slipping the bills in cocktail glasses behind the bar, the money adding up, even in the few minutes I was there. My father suggested that fortunes might be made at this job, that the bigger the winnings, the larger the tips. “I know valets who make as much as lawyers and shrinks,” he said.

I felt a familiar sense of inadequacy about my tall, skinny, relatively hairless frame. The pool boys were all in their twenties, their faces and chests stubbled, sideburns fluffing their jawbones, wearing Hawaiian trunks and white Caesar’s Palace T-shirts, laughing raunchily at the bar with a pretty bartender. This pool wasn’t very large or deep, and it was hard to imagine having to rescue anyone the way I had earnestly practiced in my YMCA classes. I tried to imagine myself doing what these men were doing; it didn’t seem hard. I’d been a motivational speaker at six, telling inspirational stories to lure people into my parents’ cosmetics pyramid scheme, a “breast batterer” at a fast-food chicken place at fourteen, a movie projectionist at a non-union theatre at fifteen, a barback at a country and western nightclub at sixteen, and I had for the past year made and scooped ice cream and built sandwiches at a Swensen’s. Everywhere I’d worked, I’d been among the youngest there, usually too young, and that had never made much of a difference. But this was Las Vegas. This was Caesar’s Palace. A small fish in a too large pond—or pool.

Read an Excerpt from Corrina Carter’s “In the Foaling Barn” in AJ 2015 ON SALE NOW

Posted: June 22, 2015 Filed under: Alligator Juniper Leave a commentFrom Corrina Carter’s “In the Foaling Barn,” 2015 Fiction Finalist

Robert Palton, who lived several miles from Live Oak Road and was eight when Mrs. Burns’ mare died, was among the children who had visited her regularly. He first became conscious of death while staring into the pit at her ruptured forehead. Unable to temper the unnaturalness of the figure sprawled on the bottom of the ditch with memories of an animal that, in life, had made him long for her pink tongue to sweep sugar from his palms, he began to associate horses with mortality. While his peers either existed in an uncritical state that did not allow for morbid concerns or feared conventional harbingers of death—reapers clad in hoods that augmented their facelessness and angels washed in an artificial glow—Robert dreaded the appearance of an equine ghost. It was gray, like Mrs. Burns’ mare. The boy imagined that everyone saw it before he or she died. It materialized in a field of threadbare grass, gazing directly at its victim. Unlike the tropical fish Robert had observed in the home of his pet obsessed neighbors, the Halsteds, which tapered into vertical footballs when viewed head-on, the horse fattened as it faced forward. It was not noble or fierce, but a beast worn by labor, its muzzle hanging between the raggedy balls of its knees, its ears pinned so neatly that they disappeared into the ridge of its neck. Even the white-lashed eyes were flat with apathy. Sometimes when Robert was woken by an illusion of falling during the night, it seemed that his bed had transformed into rolling vistas of horse’s hair, growing forever, doubling back to wrap him in silver filaments, as if he were a silkworm struggling to burst from his pupal casing.

Read an Excerpt from Justin Chrestman’s “Astronaut House,” Winner of the 2015 Annual Award in Fiction

Posted: June 20, 2015 Filed under: Alligator Juniper Leave a commentFrom “Astronaut House” by Justin Chrestman of Houston, TX, 2015 National Fiction Winner

Then suddenly it was like the world had stopped its spinning and left us going forward and I could hear the tires catching against the road gripping for grim life. The seatbelt held me like a strong arm as the cigarette flew from Bonnie’s mouth and exploded in sparks against the windshield. Nash had stopped right in the center of the highway. He unbuckled and got out of the car and stood in the road. He lifted up his pant leg and I saw a gun holstered to his ankle.

Bonnie looked out the rear window searching probably for the lights of the car that would at any minute come over the horizon and crash us into oblivion. Her long hands grabbed at her belly as though the baby might at any minute fly forward and out and away from her forever.

You’re doomed, Nash said. But he wasn’t talking to us. He aimed his pistol into the night. I expected to hear a loud bang but when he pulled the trigger there was just a whisper of sound. It looked real but it was only an air gun.

About this time Bonnie began to curse. Low words spoken so close they all wrecked into each other and became one big four letter pile up. Nash ran up the road and picked something up.

Before he got back in the car he threw the dead jackrabbit next to me in the back seat. It had a little bald spot on its head where the pellet must have hit. One of its legs twitched a bit but it was pretty dead.

Bonnie’s curses became louder.

It couldn’t be helped, Nash said. Nature is my sworn enemy.

Read an Excerpt From Michael Palmer’s Essay, “What Else” in AJ 2015 ON SALE NOW

Posted: June 17, 2015 Filed under: Alligator Juniper Leave a commentCreative Nonfiction Finalist Michael Palmer of Lubbock, TX : What Else:”

“I lived in a tiny basement apartment in Orem, Utah with one roommate. The place was enough of a shithole that even my rosy vision, enhanced by the excitement of living away from home for the first time, wouldn’t allow me to spin it as anything else. It had stained, maroon carpet, and the “walls” that made up our two “bedrooms” were flimsy beige dividers, similar to the cubicle dividers at Western Wats. We shared a bathroom; it looked like there had once been a medicine cabinet in there, but it had been ripped from the wall. Otherwise there was a loosely secured sink and an old bathtub with a showerhead that had been installed by hobbits.

The upstairs of the house was rented by a group of four guys who were in a Christian (“NOT Mormon”) metal band called Adjacent to the Lord. They practiced in the garage, and when they would play, the cereal bowls on our coffee table would shake and vibrate, Godzilla-style.

My roommate was a transgendered woman named Erin. We’d grown up together, and when we first signed the lease, she still publicly identified as a man and went by Chris.

One night, drinking coffee at the Village Inn up the street, just as the caffeine fidgeting started and I thought we were ready to leave a tip and walk back home, she asked me if I’d ever heard of gender dysphoria.

The answer was no, but since the question wasn’t about our usual topics of girls, possible road trips, or hypotheticals about who would win in a fight, I didn’t even say that. Sensing something was coming, I just looked at my speckled mug half full of coffee. In the two am diner light, the coffee looked like grease. I stirred, as if that was a response.

Read Rosemary Jones’ “The Particulars” in Alligator Juniper 2015, On Sale Now!

Posted: May 6, 2015 Filed under: Alligator Juniper, Poetry, Prescott College, Winners, Writing Leave a commentFirst Place Winner in Creative Nonfiction: “The Particulars” by Rosemary Jones of Seattle, WA:

One summer when he had gone mad with drink and despair, he found me in my flat on a long straight city road where the smell of trucks replaced the smell of hops. I complained of an aching back. He cupped his hands around my skin without touching me. Heat pulsed from his palms, as if he knew how to heal everyone except himself.

I am not where I should be with all this. He liked giving presents. He gave me a small wooden box I don’t have anymore. He gave me a large pewter Celtic brooch when I was about to leave overseas—to be married, as it turned out. Later he sent me a care package of tea tree oil and eucalyptus oil. Two Australian essentials. I still have the bottles, it takes more than a decade to use them. I didn’t give him presents. I listened. I did not listen enough. I am sorry, sorry, ever sorry. Before I left, I mentioned I hoped to have a child. Heavens, he said, you need to run up and down hills for that. He was being helpful, funny, full of kindness. He had stopped drinking, cold turkey, a new permanence. And a lonely one. In the end, my husband and I found our children in a different way, there was no need to run up and down hills or gullies. Back in my old world, I met him with one of them in tow. She was as tiny as a present. We went out to lunch. Asian fusion. He asked if I’d like a glass of wine. I declined. I didn’t want him to be tempted, but I needn’t have worried. He sniffed wine with his mates, he said, but never drank it. I ordered dessert, and that pleased him. We should have done this again, but in the future that was to come, we—not him—had another child. When we visited, we were always taking them in and out of grandparents’ gates, balancing our irregular, double-hemisphered boat. For years I did not contact him. I had my own particulars. I forgot about his.

Order Alligator Juniper 2015 here.